|

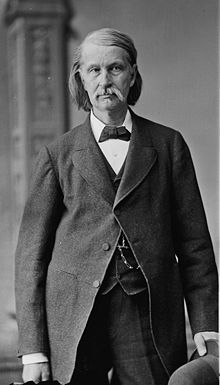

| President Lincoln |

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Washington, January 1, 1862.

Washington, January 1, 1862.

General McClellan will be glad to see you to-morrow. Please come as early in the day as you can.

S. WILLIAMS,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

WASHINGTON CITY, January 1, 1862.

General McClellan should not yet be disturbed with business. I think you better get in concert with General Halleck at once. I write you to night.* I also telegraph and write Halleck.

A. LINCOLN.

Louisville, January 1, 1862.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, President: There is no arrangement between General Halleck, and myself. I have been informed by General McClellan that he would make suitable disposition for concerted action. There is nothing to prevent Bowling Green being re-enforced from Columbus if a military force is not brought to bear on the latter place.

D. C. BUELL,

Brigadier-General.

WASHINGTON CITY, January 1, 1862.

General McClellan should not yet be disturbed with business. I think General Buell and yourself should be in communication and concert at once. I write you to-night and also telegraph and write him.

A. LINCOLN,

LOUISVILLE, January 1, 1862-11 p. m.

President LINCOLN: I have already telegraphed General Halleck with a view to arranging a concert of action between us and am momentarily expecting his answer.

D. C. BUELL,

Brigadier-General .

SAINT LOUIS, MO., January 1, 1862.

I have never received a word from General Buell. I am not ready to co-operate with him. Hope to do so in few weeks. Have written fully on this subject to Major-General McClellan. Too much haste will ruin everything.

H. W. HALLECK,

Major- General.

Official Records, Series I., Vol. 7, Part 1, Page 526.

Events conspired to push President Lincoln further into military affairs. The Committee on the Conduct of the War, dominated by Republicans and pro-war democrats such as Andrew Johnson, had just come into being and was flexing its muscles against an Army command structure most members believed was slow to act and less than committed to abolishing slavery and punishing the rebellious states. Lincoln had been pressing McClellan for a movement on the Occoquon to flank the Confederates out of Manassas and eliminate the humiliation of Confederate batteries on the Potomac, and McClellan was slow to move and now in bed with typhoid fever. Lincoln, rather disingenuously, represented McClellan as being unable to conduct business when (as the first memo shows) he was still meeting with his generals on a limited basis. He wanted Buell to move to give relief to eastern Tennessee and Halleck to threaten Columbus to fix Confederate attention away from Buell. McClellan, already unhappy with an administration incapable of keeping military secrets, now had more serious challenges to contend with, a President who fancied himself a strategist and a restive Congress, many of whom wanted to redefine the nature of the war.