|

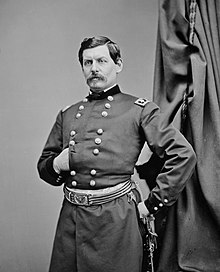

| General George B. McClellan |

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Camp near Harrison's Landing, Va., July 7, 1862

Camp near Harrison's Landing, Va., July 7, 1862

The time has come when the Government must determine upon a civil and military policy covering the whole ground of our national trouble. The responsibility of directing the whole course of national affairs in regard to the rebellion, must now be assumed and exercised by you, or our cause will be lost. The Constitution has given you power sufficient even for the present terrible exigency.

This rebellion has assumed the character of a war. As such it should be regarded, and it should be conducted upon the highest principles known to Christian civilization. It should not be a war looking to the subjugation of the people of any State

In any event, it should not be at all a war upon population, but against armed forces and political organizations. Neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organization of States, or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment.

In prosecuting the war all private property and unarmed persons should be strictly protected, subject only to the necessity of military operations; all private property taken for military use should be paid or receipted for; pillage and waste should be treated as high crimes, all unnecessary trespass sternly prohibited, and offensive demeanor by the military toward citizens promptly rebuked. Military arrests should not be tolerated, except in places where active hostilities exist, and oaths not required by enactments constitutionally made should be neither demanded nor received. Military government should be confined to the preservation of public order and the protection of political rights. Military power should not be allowed to interfere with the relations of servitude, either by supporting or impairing the authority of the master, except for repressing disorder, as in other cases. Slaves, contraband under the act of Congress, seeking military protection, should receive it. The right of the Government to appropriate permanently to its own service claims to slave labor should be asserted, and the right of the owner to compensation therefore should be recognized. This principle might be extended, upon grounds of military necessity and security, to all the slaves of a particular State, thus working manumission in such State; and in Missouri, perhaps in Western Virginia also, and possibly even in Maryland, the expediency of such a measure is only a question of time. A system of policy thus constitutional, and pervaded by the influences of Christianity and freedom, would receive the support of almost all truly loyal men, would deeply impress the rebel masses and all foreign nations, and it might be humbly hoped that it would commend itself to the favor of the Almighty.

Unless the principles governing the future conduct of our struggle shall be made known and approved the effort to obtain requisite forces will be almost hopeless. A declaration of radical views, especially upon slavery, will rapidly disintegrate our present armies. The policy of the Government must be supported by concentrations of military, power. The national forces should not be dispersed in expeditions, posts of occupation, and numerous armies, but should be mainly collected into masses, and brought to bear upon the armies of the Confederate States. Those armies thoroughly defeated, the political structure which they support would soon cease to exist.

In carrying out any system of policy which you confidence, understands your views, and who is competent to execute your orders by directing the military forces of the nation to the accomplishment of the objects by you proposed. I do not ask that place for myself. I am willing to serve you in such position as you may assign me, and I will do so as faithfully as ever subordinate served superior.

I may be on the brink of eternity, and as I hope forgiveness from my Maker I have written this letter with sincerity toward you and from love for my country.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

GEO. B. McCLELLAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

Official Records, Series I., Vol. 11, Part 1, Page 73.

While the sentiments contained in McClellan's letter were representative of the views of many in the army and perhaps most Democrats in the North, he chose a very peculiar time to develop such an extensive essay for the President's consideration. He had badly lead his army, suffered tremendous losses, was essentially penned up below Richmond at Harrison's Landing, and still had a chance, albeit much lessened to continue offensive operations. At minimum he had to be alert to possible attacks from a still dangerous foe. And yet at this time, seemingly emotionally broken only days before, McClellan chooses to lecture Lincoln on what the nature of the war should be. The letter anticipates, and opposes, what Lincoln would do after Antietam with the Emancipation Proclamation. As for fighting the war in accordance with traditional rules of war, he underestimates the essential fact the very reason for the war was an intensity of ill will between the two sections. The forces of vengence, represented by the Republicans, might have been held back by victory but would not stand idle when generals such as McClellan suffered defeat.

No comments:

Post a Comment