|

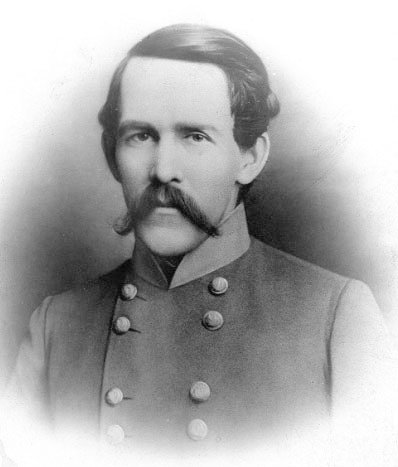

| General William T. Sherman |

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE TENNESSEE, Vicksburg,

January 31, 1864.

Major R. M. SAWYER,

Asst. Adjt. General, Dept. of the Tennessee, Huntsville:

DEAR SAWYER: In my formed

letters I have answered all your questions save one, and that relates to the

treatment

of inhabitants known or suspected to be hostile or "secesh." This is in

truth the most difficult business of our army as it advance and

occupies the Southern country. It is almost impossible to lay down

rules, and I invariably leave this whole subject to

local commanders, but am willing to give them the benefit of my acquired knowledge and experience.

In Europe, whence we derive our principles of war, as developed by their

histories, wars are between kings or rulers, through hired armies, and

not between people. These remaining, as it were, neutral, and

sell their produce to whatever army is in possession.

Napoleon,

when at war with Austria and Russia, bought forage and provisions of

the inhabitants, and consequently had an interest to protect farms and

factories which ministered to his wants. In like manner the allied

armies in France

habitants

whatever they needed-the produce of the soil or manufactories of the

country. Therefore the rule was and is, that wars are confined to the armies and should not visit the homes of families or private interests. But in other

examples a different

rule obtained the sanction of historical authority. I will only instance that when in the reign of

William and Mary the English army occupied Ireland, then in a

state of revolt, the inhabitants were

actually driven into foreign lands and were dispossessed of their property and a new

population introduced. To this day a large part of the north of Ireland is held by the

descendants of the Scottish emigrants sent there by William's order and an act of Parliament.

The war which now prevails in our land is essentially a war of races .

The Southern people entered into a clear compact of government, but

still maintained a species of sperate interests, history, and

prejudices. The latter became stronger and stronger till they have led

to a war, which has developed fruits of the bitterest kind. We of the

North are beyond all question right in our lawful cause, but we are not

bound to ignore the fact that the people of the South have prejudices

which form part of their nature and which they cannot throw off without

an effort of reason or the slow proceeds of natural change. Now, the

question arises, should we treat as absolute enemies all in the South

who differ from us in opinion or prejudices, kill or banish them, or

give them time to think and gradually change their conduct so as to

conform to the new

order of things which is slowly and gradually creeping into their country?

When men take arms to resist a rightful authority we are compelled to use force, because all reason and

argument

cease when arms are resorted to. When the provisions, forage, horses,

mules, wagons, &c., are used by our enemy it is clearly our duty and

right to take them, because otherwise they might be used against us. In

like manner all houses left vacant by an inimical people are clearly

our right, or such as are needed as store-houses, hospitals, and

quarters. But a question arises as to dwellings used by women, children,

and non-combatants. So long as non-combatants remain in their houses

and keep to their accustomed business their opinions and prejudices, can

in nowise influence the war, and therefore should not be noticed; but

if any one comes out into the public streets and creased disorder, he or

she should be punished, restrained, or banished, either to the rear or

front as the officer in command adjudges. If the people or any of them

keep up a correspondence with parties in hostility they are spies, and

can be punished with death or minor punishment.

These are well-established principles of war, and the people of the

South having appealed to war are barred from appealing to our

Constitution, which they have practically and publicly defied. They have

appealed to war, and must abide its

rules

and laws. The United States as a belligerent party, claiming right in

the soil as the ultimate sovereign, have a right to change the population, and it may be and is both politic and just we should do so in certain districts.

When the inhabitants persist too long in hostility it may be both

politic and right we should banish them and appropriate their lands to a

more loyal and useful population. No man will deny that the United

States would be benefited by dispossessing a rich, prejudiced,

hard-headed, and disloyal planter, and substituting in this place a

dozen or more patient, industrious, good families, even if they be of

foreign birth. I think it does good to present this view of the case to

many Southern gentleman who grew rich and wealthy, not by virtue alone

of their personal industry and skill, but by reason of

the protection and impetus to prosperity given by our hitherto moderate and magnanimous Government.

It is all idle nonsense for the Southern planters to say that they made the South, that they own it, and that they

can do as they please, even to break upon our Government and shut up the natural avenues of

trade, intercourse, and commerce.

We know, and they know, if they are intelligent beings, that as compared

whit the whole world they are but as five millions are to one thousand

millions; that they did not create

the land;

that the only little to its use and usufruct is the deed of the United

Stated, and if they appeal to war they hold their all by a very insecure

tenure.

For my part I believe this war is the result of false political

doctrine,

for which we all as a people are responsible; that any and every people

a natural right to self-government, and I would give all a chance to

reflect and when in error to recant. I know slave owners, finding

themselves in possession of a species of property in opposition to the

growing sentiment of the whole civilized world, conceived their property

in danger and foolishly appealed to war, and by skillful political

handling involved with themselves the whole South on the doctrine of

error and prejudice. I believe that some of the rich and slave-holding

are prejudiced to an extent that nothing but death and ruin will

extinguish, but hope, as the poorer and industrial

classes

of the South realize weakness and their dependence upon the fruit s of

the earth and good will of their fellow-men, they will not only discover

the error of their ways and repent of their hasty action but bless

those who persistently maintained a constitutional Governments strong

enough to sustain itself, protect its citizens, and promise peaceful

homes to millions yet unborn.

In this belief, whilst I assert of our Government

the highest military

prerogatives, I am willing to bear in patience that political nonsense

of slave rights, State's rights, freedom of conscience, freedom of the

press, and such other trash as have deluded the Southern people into

war, anarchy, bloodshed, and the foulest crimes that have disgraced

any time or any people.

I would advise the commanding officers at Huntsville, and such other

towns as are occupied by our troops, to assemble the inhabitants and

explain to them these plain, self-evident propositions, and tell them

that it is now for them to say whether they and their children shall

inherit the beautiful flank which by the

accident of nature has fallen to their share.

The Government of the United States has in North Alabama any and all

rights which they choose to enforce in war-to take their lives,their

lands, their everything-because they cannot deny that war does exist

there, and war is simply power unrestrained by constitution or compact.

If they want eternal war, well and good; we accept the issue, and will

dispossess them and plant our friends in their place. I know thousands

and millions of good people who at simple notice would come to North

Alabama and accept the elegant houses and plantations there. If the

people of Huntsville think different, let hem persist in war

three years longer, and then they will not be consulted. Three years

ago by a little reflection and patience they could have had a hundred

years of peace and prosperity, but they preferred war; very well. Last

year they could have saved their slaves, but now it is too late.

All the

powers of earth cannot restore to them their slaves, any more than their dead grandfathers.

Next

year their lands will be taken, for in war we can taken them, and

rightfully,too, and in another year they may beg in vain for their

lives. A people

who will

persevere in war beyond a certain limit ought to know the consequences.

Many, many peoples with less pertinacity have been wiped out of national

existence.

My own belief is, even now the non-slave holding

classes of the South are alienating from their associates in war. Already I hear recrimination. Those who have property left should take warning in time.

Since I have come down here I have seen many Southern planters who now

hire their negroes and acknowledge that they could part in peace. They

now see that we are bound together as one nation by indissoluble ties,

and that any interest or any people that set themselves up in antagonism

to the nation must perish. Whilst I would not remit one jot or tittle

of our nation's right in peace or war, I do make allowances for past

political errors and prejudices. Our national

Congress and

supreme courts

are the proper avenues on which to discuss conflicting opinions, and

not the battle-field. You may not hear from me again, and if you think

it will do any good, call some of the better people together and explain

these, my views. You may even read to them this letter and let them use

it so as

to prepare them for my coming.

To those who submit to the rightful law and authority all gentleness and

forbearance; but to the petulant and persistent secessionists, why,

death is mercy, and the quicker he or she is disposed of the better.

Satan and the rebellious saints of Heaven were allowed a continuous

existence in hell merely to swell their just

punishment. To such as would rebel against a Government so mild and just as ours was in peace, a punishment equal would not be unjust.

We are progressing well in this quarter, though I have not changed my opinion, that

although we may soon assume the existence of murder, and robbery will cease to afflict this region of country.

Truly, your friend,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

Official Records, Series I, Vol. 32, Part 2, Pages 278-281.

Sherman had an understanding of the changes his arrival would bring and no small amount of ego. It is not clear from the letter exactly what his views are regarding the conduct of war, but as he gains momentum it becomes more clear he was inclined toward taking a heavy hand to civilians in his path. The idea of banishing civilians and replacing them with a population more in tune with Northern views went beyond anything suggested by the administration.